Understanding the Acute Chronic Workload Ratio: A Key Metric for Injury Prevention in Ski Racing

When it comes to performance and injury prevention in ski racing, understanding how to balance your training load is critical. One of the most widely recognized tools for monitoring and managing this balance is the Acute Chronic Workload Ratio (ACWR). Originally developed for high-intensity sports such as soccer, rugby, and American football, the ACWR can be applied to any sport that requires rigorous physical preparation—including ski racing.

In this blog, we’ll break down what the Acute Chronic Workload Ratio is, how it’s calculated, and why it's so important for ski racers, particularly during the off-season. We’ll also explore its connection to injury risk and highlight the ideal ratios that promote peak performance while minimizing the likelihood of injuries.

What is the Acute Chronic Workload Ratio (ACWR)?

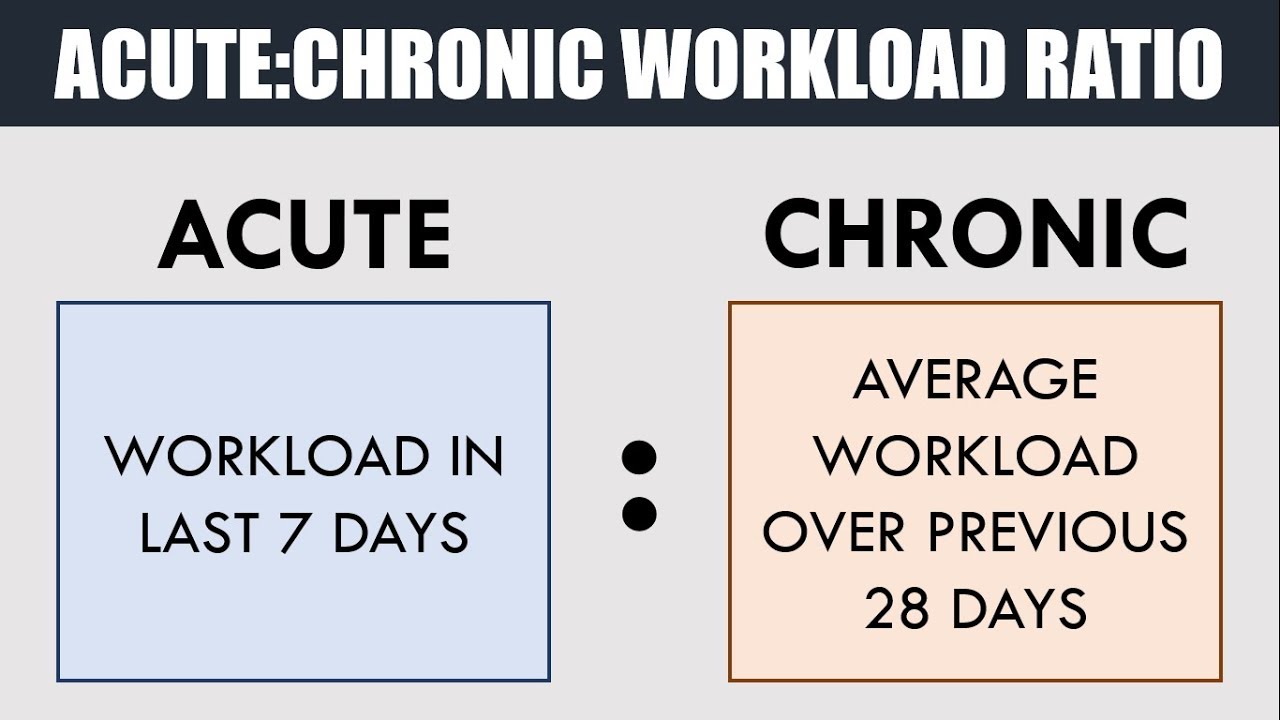

The Acute Chronic Workload Ratio is a method used to compare an athlete’s recent workload (acute) to their longer-term workload (chronic).

- Acute workload refers to the short-term physical demands placed on the body, typically measured over a week or 7 days.

- Chronic workload, on the other hand, reflects the athlete’s average physical load, built up over a longer period—usually around four weeks or 28 days.

The ACWR is calculated by dividing the acute workload by the chronic workload. This ratio gives coaches and athletes insight into whether their current workload is increasing too quickly, which can increase injury risk, or whether they are maintaining a healthy training balance that supports performance improvement.

What do we mean by "Workload"?

In the context of sports and athletic performance, workload refers to the total physical and physiological stress placed on an athlete during training or competition. It encompasses both:

- External Load—the measurable aspects of physical activity like distance covered, duration, speed, or weight lifted.

- Internal Load - the body's response to this activity, such as heart rate, perceived exertion, or muscle fatigue.

Load can be measured through a combination of tools like GPS systems e.g. Catapult, heart rate monitors, accelerometers, and subjective reporting methods like the Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) to capture both the external and internal demands of training or competition.

How to Calculate ACWR: A Simple Example

Let’s take an example from a running-based sport to simplify the concept:

- Suppose you're preparing for a Park Run by running 5km daily. Your acute workload over the past 7 days would be 35 km (5 km per day × 7 days).

- Now, let’s assume your chronic workload—the average distance you’ve run over the past four weeks—is 25 km per week.

To calculate the ACWR, divide the acute workload by the chronic workload:

ACWR = 35/25 = 1.4

This means your acute workload is 1.4 times higher than your chronic workload, providing insight into how your body is adapting to increased training.

The Impact of ACWR on Injury Risk

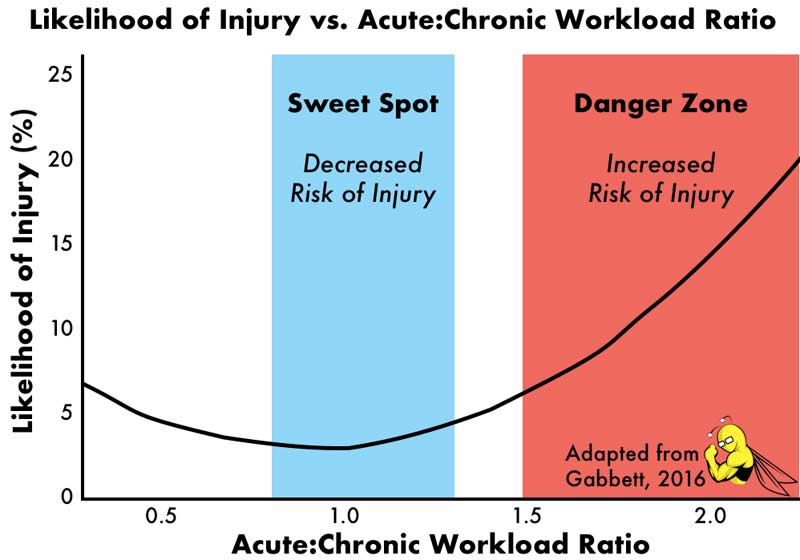

Monitoring the ACWR is crucial because it helps athletes avoid the two extremes of training: undertraining and overtraining. Research shows that an ACWR that’s too high or too low can increase the likelihood of injury.

- High Injury Risk: A ratio greater than 1.5 suggests that an athlete’s acute workload has increased too quickly compared to their chronic workload, creating a higher risk for injury. In this case, your body has not had enough time to adapt to the sudden increase in physical stress, making muscles, tendons, and joints more susceptible to strain. However a ratio <0.8 also confers an increase risk of injury.

- Lowest Injury Risk: Research indicates that an ACWR between 0.8 and 1.3 is optimal for minimizing injury risk while still promoting fitness gains. This range reflects a healthy balance where the workload is challenging but not overwhelming for the body’s current level of conditioning.

Maintaining an ACWR within this range allows athletes to progress safely while gradually building the strength and endurance needed for high-intensity sports like ski racing.

The Importance of Off-Season Training for Ski Racers

Ski racing demands strength, endurance, and agility. Therefore, it’s crucial to build up a strong fitness foundation during the off-season to prepare for the intensive nature of ski racing camps.

By maintaining consistent training in the off-season—whether it’s through running, strength training, or conditioning exercises—ski racers can ensure that their chronic workload is sufficiently high when the season starts. This reduces the risk of overloading the body once ski-specific training intensifies.

If you skip off-season training, your chronic workload will be lower, meaning that even moderate increases in training during ski camps could push your ACWR into a high-risk zone for injury.

Why is it challenging to measure ACWR in ski racing?

While the Acute Chronic Workload Ratio (ACWR) is a valuable tool for many sports, measuring it accurately in ski racing presents several unique challenges. Unlike sports such as soccer, rugby, or running, where workload is typically measured by time spent training, distance covered, or intensity, ski racing involves a more complex set of variables.

- Varied Terrain: Ski racing takes place on different slopes with varying levels of difficulty, surface conditions (ice, powder, slush), and incline. The same workout on a different course can have a vastly different impact on the body.

- Environmental Conditions: Weather conditions, including snow quality, altitude temperature, and wind, can significantly affect the intensity of a training session. For example, skiing on hard, icy snow is far more physically demanding than skiing on soft, groomed snow.

- Technical Complexity: Unlike sports where workload is determined largely by physical output, ski racing requires precise technical skills. Improving technique, working on turns, and optimizing ski angle or speed can increase mental fatigue, but this doesn’t always translate directly into physical workload that can be easily quantified.

In team sports like soccer or rugby, workload is often measured using GPS devices that track distance covered, speed, and acceleration. However, ski racing lacks a universally accepted external load metric due to the sport’s nature. While some ski racers use wearable technology like heart rate monitors or GPS systems to track certain metrics (such as speed or elevation gain), these measurements don’t capture the full spectrum of effort exerted during a run.

Final Thoughts: A Balanced Approach to Training

The Acute Chronic Workload Ratio is a valuable tool that helps athletes and coaches monitor training loads to reduce the risk of injury. By keeping the ACWR between 0.8 and 1.3, athletes can ensure they are pushing their bodies hard enough to improve but not so hard that they increase their risk of injury. For ski racers, off-season training is essential to maintain an optimal chronic workload, allowing for smooth transitions into more intense training periods like race camps.

As you prepare for your next season, remember to balance your acute and chronic workloads carefully to ensure peak performance and reduce your chances of injury.

References

- Gabbett, T. J. (2016). The training-injury prevention paradox: should athletes be training smarter and harder? British Journal of Sports Medicine, 50(5), 273-280. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-095788

- Hulin, B. T., Gabbett, T. J., Lawson, D. W., Caputi, P., & Sampson, J. A. (2016). The acute:chronic workload ratio predicts injury: high chronic workload may decrease injury risk in elite rugby league players. British journal of sports medicine, 50(4), 231–236. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-094817

- Hulin, B. T., Gabbett, T. J., Blanch, P., Chapman, P., Bailey, D., & Orchard, J. W. (2014). Spikes in acute workload are associated with increased injury risk in elite cricket fast bowlers. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 48(8), 708-712. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2013-092524

- Malone, S., Owen, A., Newton, M., Mendes, B., Collins, K. D., & Gabbett, T. J. (2017). The acuteworkload ratio in relation to injury risk in professional soccer. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 20(6), 561-565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2016.10.014

Written by Jazzy Bullen (BSc. Biomedical Sciences, MSc. (pre-reg) Physiotherapy, MHCPC, MCSP).